Q. What can schools and parents do to help children?

A model of learning through work

Let's focus on the idea of basic respect for each other, basic value systems. We can always catch up with academics. I have seen children of age 14 who didn’t know how to read the alphabet, catch up academically. I believe what really helped them was to know that they are good people, that they are capable, and that other people love them. This helped them love themselves. Then reading happens, math happens. In my opinion, lack of self-worth is the root cause of lack of learning.

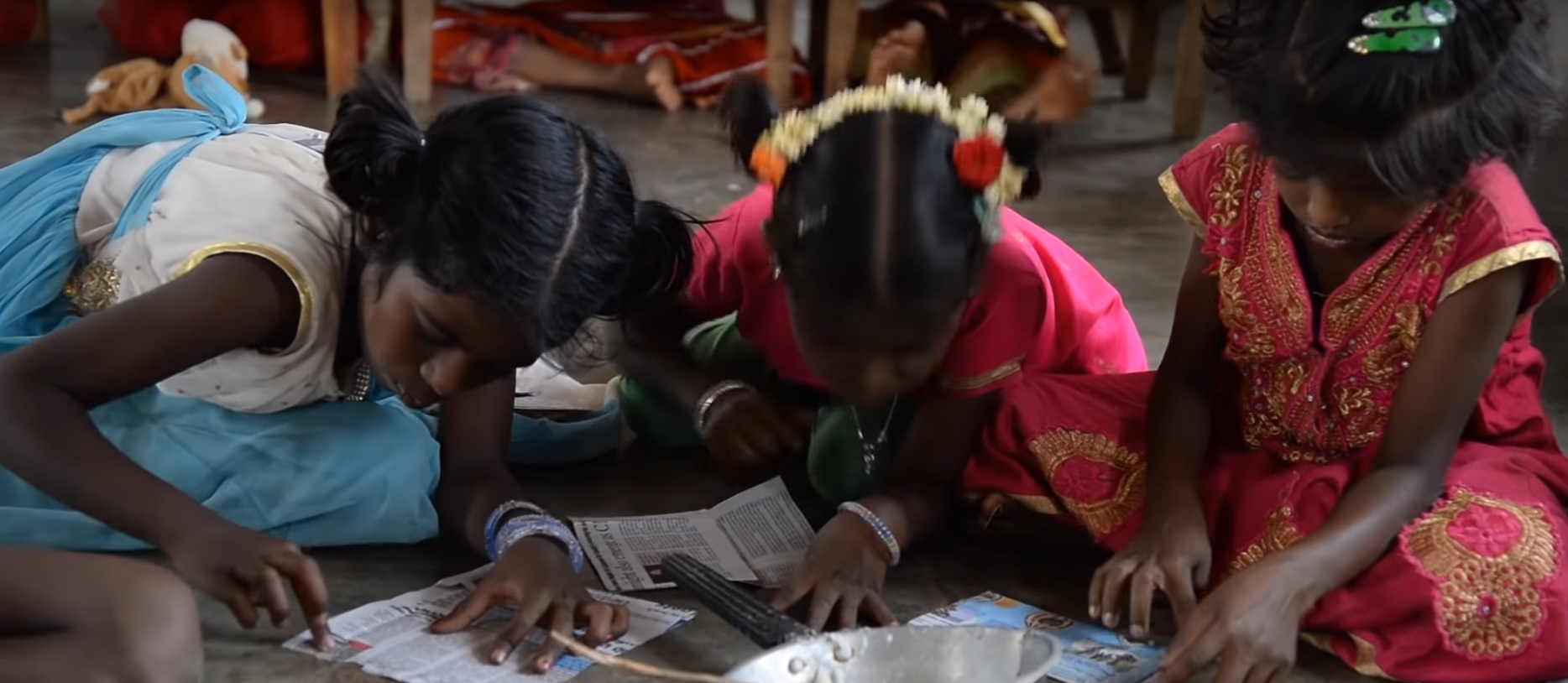

At Puvidham, education is based on work. Conventionally, we tend to segregate the child from our social life thinking that their job is to just study. However, if you observe that is not what the child wants. From the age of two, the child wants to be treated like an adult. The child wants to engage in real life activities. The child wants to participate in our life, make the “chapati” and so on. But we shoo them away. However, If we engage them, they will feel like they are contributing to life meaningfully — their inclusion in daily activities increases their self-worth. By involving children, we can start teaching them about where the food comes from, about conscious consumerism, about keeping the environment healthy by avoiding the use of plastics, and about localization. Such learning is far more important than teaching them “ABCD’ and “1234.”

At Puvidham, we allow children to lead, to learn. We engage them in everyday work too. We delegate responsibilities. They learn to manage their time. They learn to manage themselves. Traditionally, we don’t involve children in activities at our schools and homes – then we find our managers are lousy, they cannot manage time or themselves and that they are not empathetic with other human beings. That is what we are trying to change here. We allow children to remain in touch with their instinct. Allow that instinct to grow into intuition which can guide them for the rest of their lives.

Q. There will be times when children engage in behaviors that could harm them. How do you protect them without imposing your ideas on them?

Behaviors can be changed through dialogue, not imposition

We have two different groups of children – those who live here, and those who come from home. Parents of the latter group tell us that children are often addicted to TV. Such behaviors in children are somewhere the fault of the adults. At some point the adult finds it convenient to give food and place the child in front of the TV. To address such behavioral issues, I speak to the child but I also ask the parent to take responsibility and change their habits at home.

I ask children to record what times they watched TV. They also have to tell me what they watched and what they learnt. They slowly realize they don’t learn a lot but they are wasting a lot of time. They also begin to realize that while they may find TV watching to be pleasurable it is actually not a very useful activity. At this point, we ask them whether it makes sense for them to be seeking pleasure the whole day, and who will take care of their work, for example on the farm, and so on. These kinds of participatory conversations and analysis with the children helps us negotiate together how much time they can watch TV safely. The children may ask for 2 hours. We have to negotiate that two hours in one go may be too much as it tends to ruin their eyes. We then arrive at a compromise — they can watch TV in half hour slots – half-hour before lunch, half-hour in the evening. Another half-hour in school while they are working on something. In this way, we gradually help day scholar children with TV addiction.

In contrast, the children in the residential program don’t have access to TV every day. But we don’t want to fully deprive them either, because they can get addicted when they go back home. So, we help them develop a balanced approach to media. We watch one film a week, making sure we select a good film. We also have a conversation after the viewing to ensure they are thinking intelligently about it – what was the theme of the film, which character do they identify with, how would they have wanted the film to end. This shifts the experience from passive consumption to active engagement. It helps children to develop the skills to critically analyze whatever information they are consuming.

We also talk to children about what the media does to them – for example, when they watch advertisements on TV, help them realize that they are being manipulated by the advertiser. Advertisements are meant to create a sense of fantasy and entice people to buy products. For instance, we help children see for themselves that they don’t grow 6 inches taller after drinking a malt drink. We tease them sometimes – “They are fooling you, do you have only that much intelligence? If you are alright being fooled, then I cannot help you.” They usually protest that they are capable of thinking and they don’t want to be fooled. Through regular reinforcement with multiple examples, we help children arrive at the understanding that a lot of what is being advertised is make believe and that they will end up wasting their time and money if they get taken in by ads.

Q. Will such ideas work in mainstream systems which have the pressure of syllabus, exams and so on?

A new way of looking at evaluation

I feel the ghost of evaluation and grading needs to be addressed. Historically, it was introduced as a “filtration system” to get rid of all those who are not “good slaves” and catch a few who are “perfect slaves.” So, when parents come to me saying their child is not fitting in the system, I congratulate them by saying, “your child is intelligent.” Currently, assessment is used to fill a pipeline of managers for hierarchical systems. What happens to those who do not do well in these assessments? We make them feel less. We dehumanize them. They become dangerous to society because when someone is not happy with themselves, they cannot give happiness to others. They don’t love themselves, so they cannot love others. This is where the violence and corruption in society starts. When such children come to power, they abuse it to the fullest.

To me, it seems that the purpose of evaluation is to ruin society. If we didn’t have evaluation, we would have a very beautiful society where each part plays its role. It is like our body, where each organ knows its function and performs its best. If you want to have a society where you don’t have to lock your doors, where everyone has equal amounts of material goods and equal amount of respect, if you want a truly egalitarian society, you need to get rid of current forms of evaluation.

My definition of evaluation is different. Self-evaluation is a part of life. Evaluation of another is also part of life. Even a two-year-old child will look at another child and try to decide whether he should act a certain way, or the consequences of doing something. The problem arises when evaluation determines your self-worth. When it passes judgment on you. Especially in early childhood up to age of 14 when your character is being built. You don’t need marks to evaluate. Feedback can be given using other means, like circle time in class. For instance, there could be a child who needs feedback that he/she talks all the time and that disrupts what the class wants to do. This should be a part of a democratic process where everyone gives and receives feedback. In fact, the teacher should open herself up to feedback first. When children see the teacher receiving feedback openly, accepting it, they will follow.

The change these systems can bring about is much more powerful than what exams can do — because we are not passing judgment, we are involving the child in the thought process and helping them change their understanding. We need to be understanding, compassionate, and open to dialogue. This helps us develop individuals who understand themselves and are confident of their abilities. Then they will perform. There is no other way.